When the Dharma Met the Irishwoman in Me

I was born in Dublin in the 1970s. It is a small city on a small island, but nothing about it felt small. Ireland then still carried an ache that hummed beneath daily life like an underground drumbeat. It was only a few decades out from independence. To the north, Northern Ireland was in the thick of The Troubles. There were soldiers on the streets of Belfast and Derry/Londonderry, armoured cars, bombings reported on the evening news. It was grief and rage tangled together, unresolved, unspoken.

Sometimes you don’t know yourself until someone more experienced than you, dharmically, names you accurately enough to break your own heart open and hand you back to yourself, newly claimed, lighter than you left.

And everywhere, the shadow of colonization lingered.

England had colonized the land.

The Church had colonized the soul.

Catholic authority shaped the moral imagination, the tone of guilt, compliance and obedience, the deep inheritance of silence, especially around pain. There was a national habit of both humour as medicine and distraction. You laughed, you pushed on, you didn’t stare too long at the wound. In my circles, family gatherings, school corridors, pubs, and neighbourhoods, the past was referenced in jokes. It was rarely explored in truth. Trauma was nicknamed, coated with sarcasm, tucked away under the tablecloth.

And there I was.

A serious, sensitive, inward-burning girl who felt like she was drowning in a sea no one else seemed to notice. I wanted healing in my family. I wanted to name the grief, to trace the lineage of subjugation, the repression, the shame smuggled in through colonization and religion. But every time I edged toward the deeper conversation, I was met with:

“Too serious, Karen.”

“Too sensitive, Karen.”

“Lighten up, Karen.”

I mistook the denial of pain for the absence of it.

I left the island thinking geography was the problem. I moved to Brussels imagining a tidy Eurocratic life and a sensible career. Catch me some order, some structure, some stability, I thought. But the quieter voice in me, the one mistrusted at home, whispered again:

What you crave is not a career. It’s a spiritual teacher.

There was no Rinpoche in the classifieds in Brussels.

Nothing worked out. Every job dissolved before it began. Then I saw a role advertised in Japan, the last place on earth I would have saw myself. But the only place my soul would point. The voice said:

Apply.

So I did.

Despite the competition. Despite the absurdity. Despite the total lack of strategic logic. When I stepped onto that plane, I felt like a thousand years of Irish resistance and fear had buckled up beside me. My stomach tight with ancestral scepticism:

What am I doing? Going to Japan.

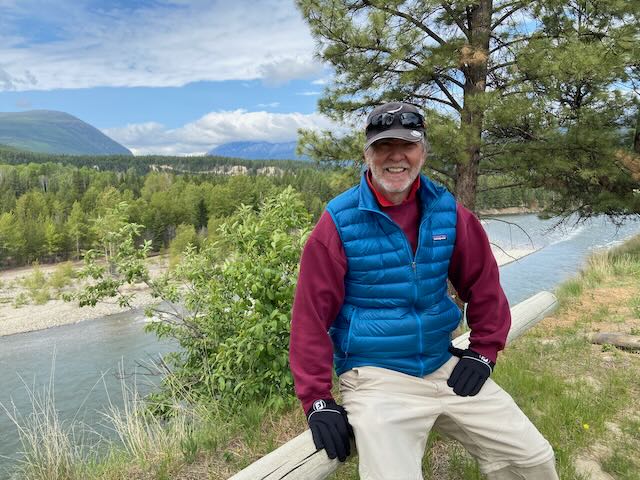

Two months later, I met my teacher, Qapel.

And the first teaching I received was not about me at all. It was a story about his own surrender. He talked about meeting his teacher, Namgyal Rinpoche. The question Namgyal posed to Qapel was simple and devastating and clean for me:

“Are you willing to be a slave?”

Not a metaphor.

Not a psychological exercise.

A medicine.

I remember thinking:

As an Irishwoman, haven’t I already inherited conditions of subjugation, repression, and Church-fostered compliance? Isn’t my whole conditioning one of involuntary slavery, spiritual occupation, comedic denial, and emotional curfew? Am I volunteering for the same thing again?

I did not yet understand the difference between imposed servitude and chosen surrender.

In the years that followed, my teacher gently, relentlessly named my states of mind:

Dissociated victim.

Perpetrator projected outward.

Warrior not yet embodied.

Freeze-flight-fawn in conversation.

Authority issues disguised as righteousness.

Tyrant emerging when desires unmet.

At first I wriggled in the naming. Then I recognized myself in it. Then I owned it. Slowly, beautifully painfully, I began to see the Irish conditioning in me:

The old story of victim = perpetrator

Looped like a harp string pulled too tight.

I realized I had always felt taken advantage of by others. It was that national undertow that mapped perfectly onto my personal psyche. And worse: when I didn’t get what I wanted, I turned tyrannical and blamed the world for failing to deliver happiness on demand. The wound was mine. The reactivity was mine. The conditioning was inherited, but the wrapping paper was personalized.

The breakthrough was not in escaping the dynamic.

It was in seeing that I was the dynamic and choosing to step out of the projection.

For the first time, I understood the freedom that comes when you stop outsourcing the villain of your disappointment.

Now, when I bow in surrender, it is not obedience and compliance to occupation.

It is loyalty to liberation.

I didn’t fly away from Ireland.

I flew toward my teacher because, finally, someone would help me surface, speak, surrender, and stand.

Sometimes you don’t know yourself until someone more experienced than you, dharmically, names you accurately enough to break your own heart open and hand you back to yourself, newly claimed, lighter than you left.

Thank you, Qapel. Thank you for your patience, love, and for never giving up on me.